Marin

Developing models together, openly

Introducing Marin: An Open Lab for Building Foundation Models

Open-source software is a success story: It powers the world’s digital infrastructure. It allows anyone in the world to contribute based on merit. It leads to greater innovation, collaboration, and security.

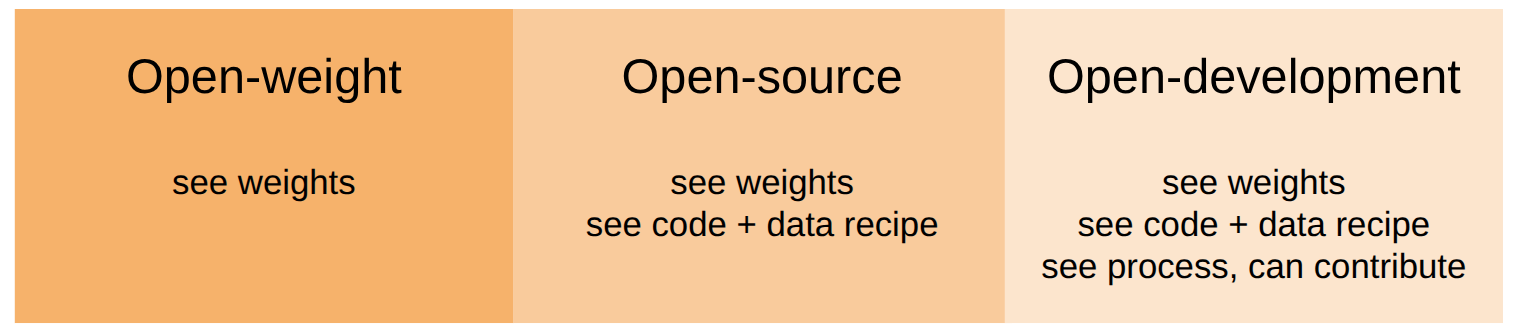

Open-source AI is not there yet. We have open-weight models (e.g., Llama, DeepSeek, Gemma), sometimes mistakenly called open-source models, but the code and data (recipe) used to produce the model are not released. There has been a movement over the last few years to build open-source models. Eleuther AI, Allen Institute for AI (AI2), Hugging Face, BigScience, BigCode, LAION, DataComp-LM, MAP-Neo, LLM360, Together AI, NVIDIA, and others have taken the path (so far) less traveled. These teams not only have released model weights, but also the code and data recipe used to produce the model. These assets have enabled others (including Marin!) to build their own models and push forward innovation.

We would like to go one step further. In open-source software, it is easy for anyone to download the code, extend it, and contribute back to the community. This is because over the last two decades, the community has developed mature tools: versioned code hosting (e.g., GitHub), continuous integration, and governance strategies. Such infrastructure doesn’t exist yet for the development of foundation models. You can’t train locally, and you can’t just log into someone else’s GPU or TPU cluster.

A new form of openness

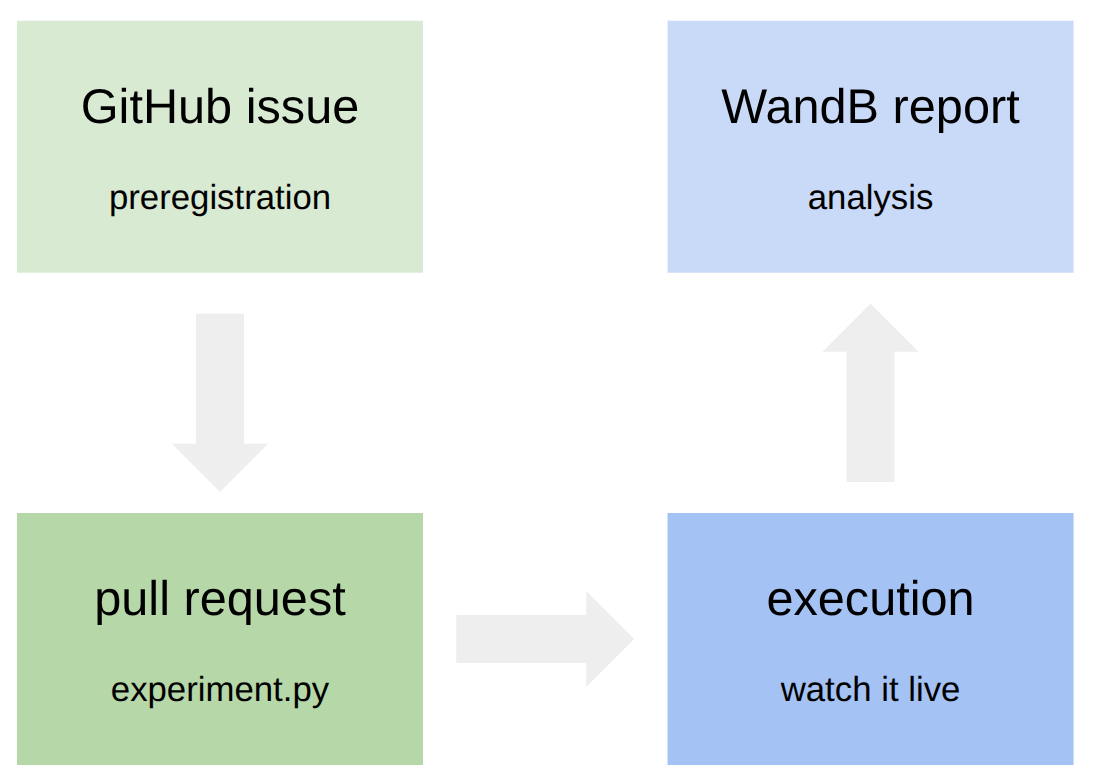

Marin is an open lab, in which the research and development of models is completely transparent from day 1 (that’s today). We leverage GitHub to organize the open lab’s efforts, piggybacking off of tools and processes developed for open-source software. Here’s how it works:

-

Each experiment (whether it be on the wishlist, currently running, or completed) is tracked by a GitHub issue—see an example. These GitHub issues serve as form of mini-preregistration, which declares the hypotheses and goals upfront.

-

To run an experiment, someone (anyone) submits a pull request (PR) specifying what concretely needs to be run. Not only does the Marin codebase contain our training and data processing code, experiments are also declared in code (see an example).

-

The PR can be reviewed by anyone (in the spirit of OpenReview for papers). The community can have a lively debate about experimental design, bikeshed details, whatever. Because the actual code is available, one can drill down into as much detail as one wants.

-

Once the PR is approved, the experiment is launched. Anyone can watch the execution live (example), which has links to WandB. Any analysis and insights are collected back into the GitHub issue.

This is a new way to do research that’s more scientific and more inclusive. We normalize making mistakes (which we all make—see all the things we messed up on our 8B run). Any negative results are in the open. There is no cherry picking. There is no ambiguity about what was run. Everything is reproducible, declared in code, and open to the community to see.

Experiments and models

Having built the infrastructure for the open lab, what do we use it for? We are driven by the fundamental research question: how do we build the best model with a fixed resource budget? Here, “best” captures some notion of accuracy, and “resources” captures both compute and data (human labor).

There is both a tension and synergy between scientific understanding and engineering the best model. This is reflected in a bifurcation in our experiments:

-

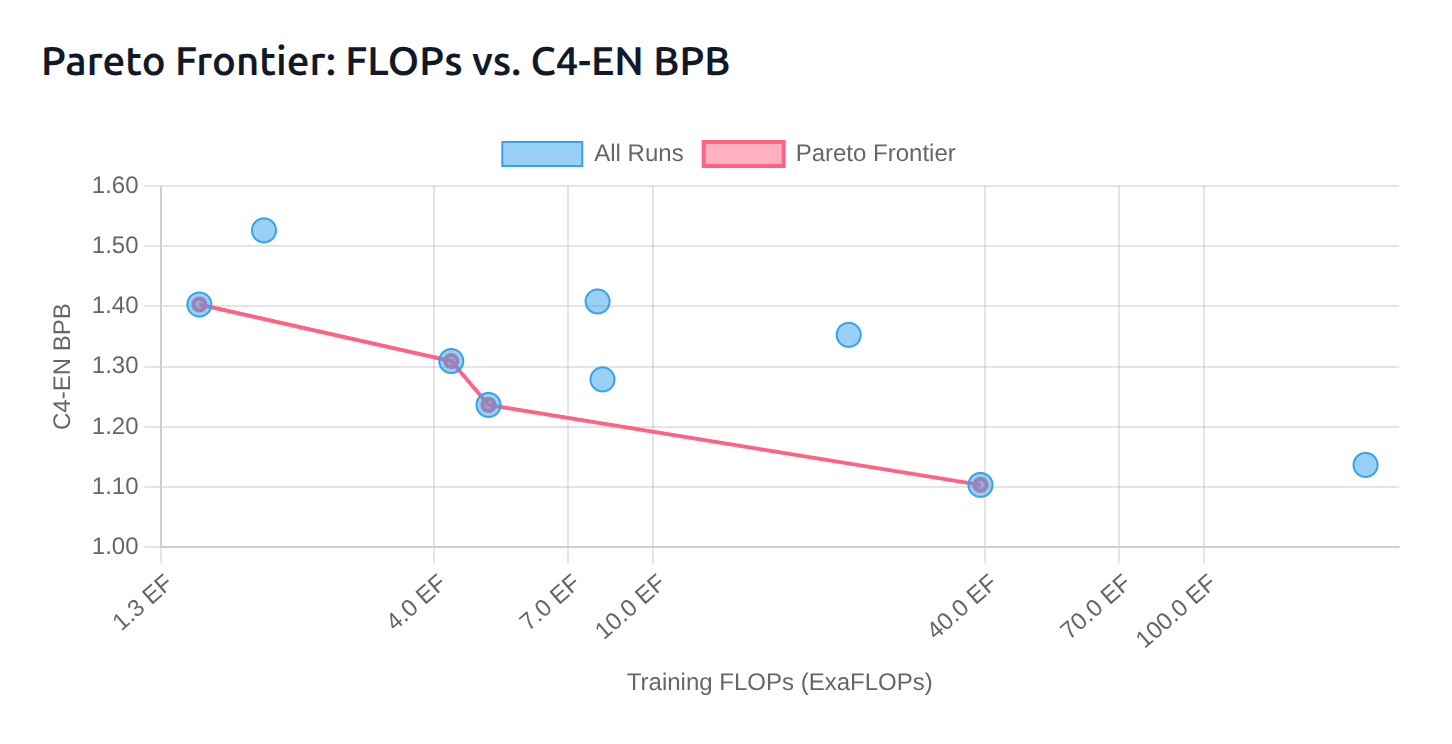

We performed controlled small-scale ablation experiments to understand one small piece of the puzzle at a time. For example, we investigated different architectures, optimizers, quality classifiers, regularization methods, and so on. We built new datasets using improved HTML to text and started doing crawling. We fit scaling laws. These experiments have the ethos of the Stanford Language Modeling from Scratch (CS336) class, in which we study every component of the language modeling pipeline.

-

We also performed a few YOLO runs which eventually led to our best models. We documented our journey in the Marin 8B retrospective, which is reminiscent of the OPT logbook (though our TPUs were nice and thankfully we didn’t have to deal with all those hardware issues). In these YOLO runs, we encountered bugs along the way and discovered new revelations about datasets, learning rates, regularization…but we just adjusted our training and kept on going. Once in a while, we would peel off to do a controlled experiment (example), which then informed us how to continue.

In the end, we ended up training Marin 8B Base (deeper-starling), with a Llama architecture (dense Transformer) for 12.7T tokens (see the full reproducible execution!). On 14 out of 19 standard base model evals (MMLU, HellaSwag, GPQA, etc.), Marin 8B Base outperforms Llama 3.1 8B Base (see full results table), but one must always be careful about interpreting evals due to train-test overlap and the non-trivial impact of prompting differences.

We also performed supervised fine-tuning (SFT) of Marin 8B Base for ~5B tokens to produce Marin 8B Instruct (deeper-starling-05-15). This model outperforms OLMo 2 on standard instruct model evals, but still fall short of Llama 3.1 Tulu—see full results table. Considering that, unlike Llama 3.1 Tulu, we have not yet done any reinforcement learning from feedback (RLHF), not even DPO, we are optimistic that we can still improve the instruct model substantially.

But don’t take our word for it—try out these models yourself! You can download both from Hugging Face or try out Marin 8B Instruct at Together AI. Please provide feedback either by submitting a GitHub issue or posting in our Discord. Or in the spirit of true open-source, you can try fixing it yourself at our Datashop.

Speedrun for the AI researcher 🏃

As an open-source project, anyone can contribute in any way to Marin. However, to add structure to these contributions, we lean on leaderboards, which have a long history of driving progress in AI. Most AI leaderboards are about benchmarking a final model, system, or product. However, we want to incentivize algorithmic innovation.

We draw inspiration from the nanogpt speedrun, which solicits submissions from the community to “train a neural network to ≤3.28 validation loss on FineWeb using 8x NVIDIA H100s” in the shortest time. Progress has been incredible: in the span of a year, the training time has dropped from 5.8 hours to just under 3 minutes.

However, it is well known that some ideas work well only at small scales, so it’s not clear which of these ideas matter at larger scale. The Marin Speedrun accepts submissions at multiple compute budgets. This allows researchers to participate at whatever compute budget is available to them. We also encourage using a scaling suite of different compute budgets, so that can fit scaling laws and assess a method based on how well it scales (what is the slope?) rather than how good it is at any one scale.

You are encouraged to try out new architectures, optimizers, and even data filtering strategies. For the initial submission, participants will use their own compute and report the metrics (in a pull request along with the code). Over time, we will offer promising submissions free compute to scale up.

Check out this example submission and get started with this tutorial!

Datashop for the domain expert 🛠️

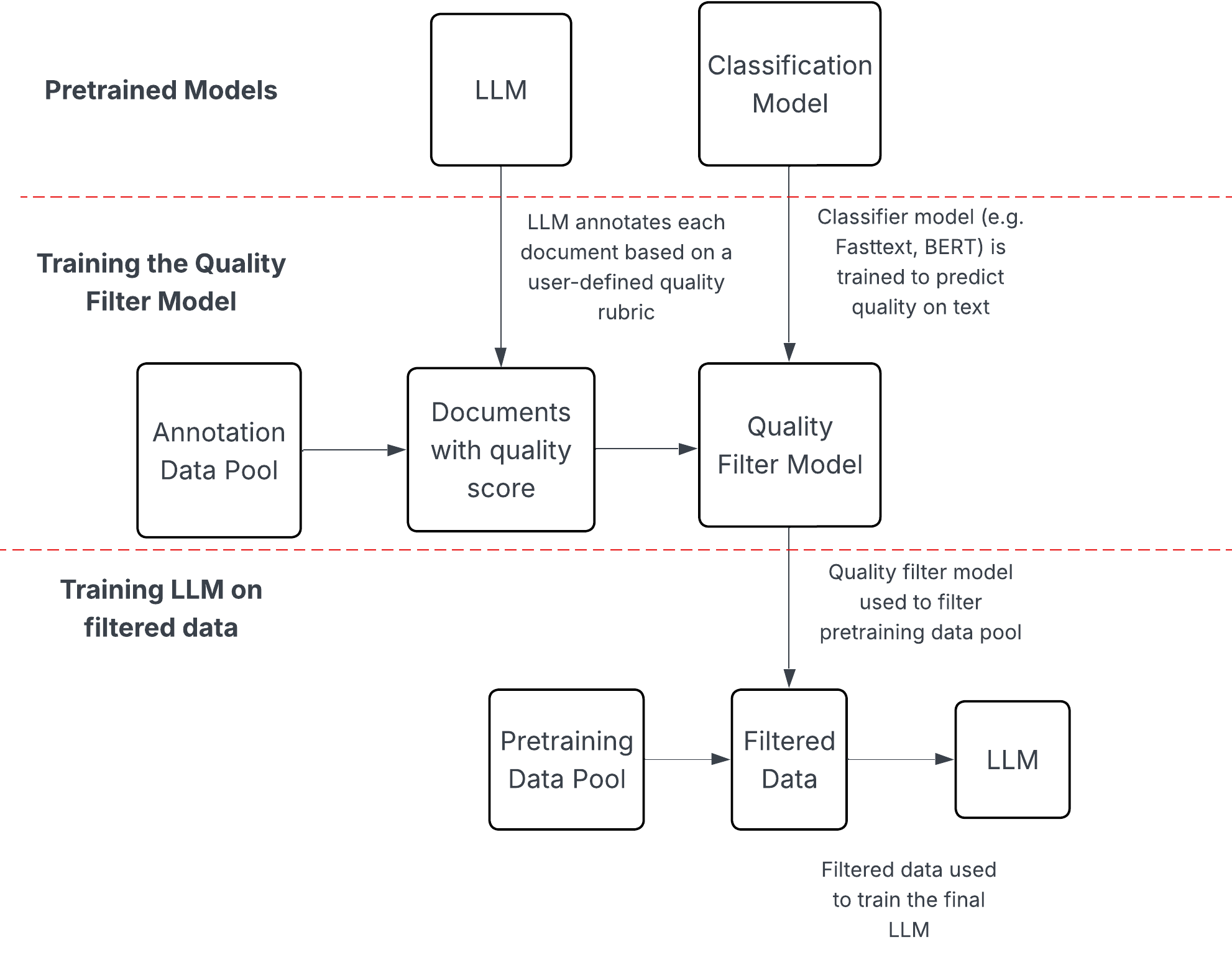

Language models can in principle do anything, but in practice they have holes. An effective way to fill these holes is to curate relevant data. We have set up Datashop to do this. Suppose you would like the Marin 8B model to improve its capabilities along some dimension (e.g., chemistry). Using Datashop, you can upload a dataset or craft a prompt that uses an existing LM to curate a relevant dataset. As before, the proposed experiment is codified in Python, submitted as a pull request, reviewed, and then executed live. Here is an example of how Datashop can be used. Datashop is a great way for domain experts, who might not necessarily have the AI infrastructure setup to contribute to making the model better. More specifically:

- You specify a prompt describing the type of data you want to obtain (e.g., FineMath prompt).

- We then prompt an LM (e.g., Llama 3 70B) to classify a subset of documents.

- We use the (document, adherence to your criterion) examples produced by the LM to train a linear or BERT classifier.

- We then run this classifier on all the documents and choose the ones that are classified positive beyond some threshold (selected examples) (negatives are just drawn from the background dataset).

- Once you have the dataset, you can fine-tune a model on it! Or you can run a controlled annealing experiment to evaluate it for inclusion during midtraining.

See the full execution of the FineMath replication experiment.

Final remarks

The future of AI should be open-source in the strongest sense: researchers and developers alike should be able to not just use AI, but to contribute directly back to it. We have built Marin, an open lab, that provides the infrastructure to help make this happen. Of course training strong foundation models requires significant resources, and building communities is hard. Nonetheless, we must try. We have benefited greatly from an open Internet, open-source software, Wikipedia, and many assets in the public domain. At one point, these were also crazy ideas that were more likely to fail than to succeed.

This is the beginning of the Marin journey. There is so much to do: we’d like to try efficient linear attention architectures, add long context support, improve performance on other domains like legal reasoning, support more languages, support multimodality, enhance reasoning with RL-based post-training, and all the ideas you have that we haven’t thought of. Come join us (Discord, GitHub) and let us deepen our scientific understanding and build the best models together!

Acknowledgements

So many people and organizations have supported Marin, to whom we are greatly indebted:

- First, we would like to thank Zak Stone and the Google TPU Research Cloud (TRC) team. Nearly all of the compute used for Marin comes from TRC. This project might not have even gotten started without their support.

- The Google JAX team, especially Roy Frostig, Sharad Vikram, Matthew Johnson, Yash Katariya, and Skye Wanderman-Milne, and Allen Wang from the TPU team helped us make good use of our TPU allocation.

- The Anyscale team, especially Robert Nishihara and Richard Liaw, helped us with Ray, which Marin builds on.

- We would like to thank Matthew Ding, Kevin Klyman, Russell Power, and Cathy Zhou for their contributions to the project.

- This work originated from the Stanford Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) and the Human-Centered AI Institute (HAI). We are grateful for their support and fostering the belief that academia has an important role to play in the era of industrialized AI.

- We would also like to thank the many people, including members of the Stanford AI Lab and Stanford NLP group, who have given advice and contributed valuable discussions.

- Thanks to the Together AI team for hosting the Marin 8B Instruct model.

- We would also like to thank Weights And Biases for logging our many, many experiments.

- Finally, we would like to give a big shoutout to the open-source community, without which Marin would simply be impossible. Organizations such as EleutherAI, Allen Institute for AI (AI2), Hugging Face, BigScience, BigCode, LAION, DataComp-LM, MAP-Neo, LLM360, Together AI, NVIDIA, and many others, have been hugely inspirational in paving the way towards truly open-source foundation models. They have released tools and datasets that have directly benefited Marin, and we can only hope to give back to the community through our efforts.